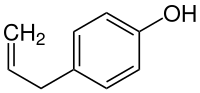

Chavicol

| Strukturformel | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | |||||||||||||||||||

| Name | Chavicol (Trivialname) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Andere Namen |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C9H10O | ||||||||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | |||||||||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 134,18 g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Aggregatzustand | flüssig | ||||||||||||||||||

| Dichte | 1,0175 g·cm−3[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Schmelzpunkt | 16 °C[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Siedepunkt | 237 °C[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| pKS-Wert | 10,23 (bei 25 °C)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Brechungsindex | 1,5441[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen (0 °C, 1000 hPa). Brechungsindex: Na-D-Linie, 20 °C | |||||||||||||||||||

Chavicol (synonym p-Allylphenol) ist eine chemische Verbindung aus der Gruppe der Phenylpropene.

Vorkommen

Es kommt natürlich im Öl des Basilikums,[1] des Betelpfeffers[1] und im Öl des Bays[3] vor. Chavicol findet sich im Zimt (Cinnamomum aromaticum).[4] Chavicol liegt in einem Massenanteil von 30 bis 40 %[5] im Öl des Betelpfeffers meist neben Terpenen vor, während es im Basilikumöl neben Estragol (synonym Methylchavicol) vorkommt.[1] Im Öl des Bay liegt es neben Eugenol vor.[3] In geringeren Mengen kommt es im Öl von Ocimum canum vor.[6] Chavicol ist ein Lockstoff für die Käfer Diabrotica undecimpunctata und Diabrotica virgifera.[1]

Natursynthese

Die Biosynthese erfolgt aus p-Cumarylalkohol.[7][8]

Eigenschaften und Verwendung

Es wirkt schwach antibakteriell, mit einer MIC von 0,125 % Volumenanteil gegen Aeromonas hydrophila und 2 % Volumenanteil gegen Pseudomonas fluorescens.[9] Chavicol wird als Duftstoff in Parfüms, in Lebensmitteln und Spirituosen verwendet.[1]

Literatur

- R. G. Atkinson: Phenylpropenes: Occurrence, Distribution, and Biosynthesis in Fruit. In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 66, Nummer 10, März 2018, S. 2259–2272, doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04696. PMID 28006900.

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j Burkhard Fugmann: RÖMPP Encyclopedia Natural Products, 1st Edition, 2000. Georg Thieme Verlag, 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-179551-9.

- ↑ Dieser Stoff wurde in Bezug auf seine Gefährlichkeit entweder noch nicht eingestuft oder eine verlässliche und zitierfähige Quelle hierzu wurde noch nicht gefunden.

- ↑ a b G. Vittorio Villavecchia: Nuovo Dizionario di Merceologia e Chimica Applicata. Band 2, Hoepli, 1977, ISBN 88-203-0529-1, S. 593.

- ↑ 4-ALLYL-PHENOL (englisch). In: Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database, Hrsg. U.S. Department of Agriculture, abgerufen am 6. August 2023.

- ↑ Alfred Henry Allen: Commercial organic analysis: a treatise on the properties. Band 2, Teil 3, S. 358.

- ↑ N. A. Vyry Wouatsa, L. Misra, R. Venkatesh Kumar: Antibacterial activity of essential oils of edible spices, Ocimum canum and Xylopia aethiopica. In: Journal of Food Science. Band 79, Nummer 5, Mai 2014, S. M972–M977, doi:10.1111/1750-3841.12457. PMID 24758511.

- ↑ NPCS Board of Consultants & Engineers: The Complete Technology Book on Flavours, Fragrances and Perfumes. Niir Project Consultancy Services, 2007, ISBN 978-81-904398-8-6, S. 89.

- ↑ D. G. Vassão, D. R. Gang, T. Koeduka, B. Jackson, E. Pichersky, L. B. Davin, N. G. Lewis: Chavicol formation in sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum): cleavage of an esterified C9 hydroxyl group with NAD(P)H-dependent reduction. In: Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. Band 4, Nummer 14, Juli 2006, S. 2733–2744, doi:10.1039/b605407b. PMID 16826298.

- ↑ Wayne R. Bidlack: Phytochemicals as Bioactive Agents. CRC Press, 2000, ISBN 978-1-56676-788-0, S. 106.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

Autor/Urheber: Asit K. Ghosh Thaumaturgist, Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

Close-up of the Betel Leaf vine (Piper betle / Piperaceae) with an extensive, spreading root system has grown in shallow water without any soil and in a controlled environment in the Everglades Atrium of the Gaylord Palms Resort & Convention Center, Kissimmee, Florida.