Chargaff-Regeln

Die Chargaff-Regeln beschreiben die Basenpaarung doppelsträngiger DNA.

Eigenschaften

Die Chargaff-Regeln wurden von 1952 bis 1968 von Erwin Chargaff aufgestellt.[1] Sie umfassen die Parität (gleiche Anzahl) von Nukleinbasen auf beiden DNA-Strängen zwischen Purinen und Pyrimidinen und die Parität zwischen Adenin und Thymin bzw. Guanin und Cytosin.

Die Chargaff-Regeln besitzen eine Gültigkeit für eukaryotische Chromosomen, bakterielle Chromosomen, Genome von doppelsträngigen DNA-Viren und archaeische Chromosomen.[2] Sie gelten auch für mtDNA und DNA von Plastiden. Für einzelsträngige DNA-Viren oder RNA gelten die Chargaff-Regeln nicht.[3] Wacław Szybalski zeigte in den 1960er Jahren, dass in den Genomen von manchen Bakteriophagen deutlich mehr A und G als C und T vorkommen.[4][5][6][7]

Erste Paritätsregel

%A = %T und %G = %C[8]

Zweite Paritätsregel

%A ≈ %T und %G ≈ %C, bei jedem der beiden Einzelstränge.[9][10]

Eine Gültigkeit der zweiten Paritätsregel wurde auch für Codons postuliert:[11]

Codons mit T.. sind paritätisch mit Codons mit ..A

Codons mit C.. sind paritätisch mit Codons mit ..G

Codons mit .T. sind paritätisch mit Codons mit .A.

Codons mit .C. sind paritätisch mit Codons mit .G.

Codons mit ..T sind paritätisch mit Codons mit A..

Codons mit ..C sind paritätisch mit Codons mit G..

Relative Anteile (%) der Nukleinbasen in DNA verschiedener Arten[12]

Ein Verhältnis, das vom 1:1-Verhältnis abweicht, deutet auf einzelsträngige DNA hin, z. B. beim Bakteriophagen φX174.

| Organismus | %A | %G | %C | %T | A/T | G/C | %GC | %AT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φX174 | 24,0 | 23,3 | 21,5 | 31,2 | 0,77 | 1,08 | 44,8 | 55,2 |

| Mais | 26,8 | 22,8 | 23,2 | 27,2 | 0,99 | 0,98 | 46,1 | 54,0 |

| Kraken | 33,2 | 17,6 | 17,6 | 31,6 | 1,05 | 1,00 | 35,2 | 64,8 |

| Huhn | 28,0 | 22,0 | 21,6 | 28,4 | 0,99 | 1,02 | 43,7 | 56,4 |

| Wanderratte | 28,6 | 21,4 | 20,5 | 28,4 | 1,01 | 1,00 | 42,9 | 57,0 |

| Mensch | 29,3 | 20,7 | 20,0 | 30,0 | 0,98 | 1,04 | 40,7 | 59,3 |

| Grashüpfer | 29,3 | 20,5 | 20,7 | 29,3 | 1,00 | 0,99 | 41,2 | 58,6 |

| Seeigel | 32,8 | 17,7 | 17,3 | 32,1 | 1,02 | 1,02 | 35,0 | 64,9 |

| Weizen | 27,3 | 22,7 | 22,8 | 27,1 | 1,01 | 1,00 | 45,5 | 54,4 |

| Backhefe | 31,3 | 18,7 | 17,1 | 32,9 | 0,95 | 1,09 | 35,8 | 64,4 |

| E. coli | 24,7 | 26,0 | 25,7 | 23,6 | 1,05 | 1,01 | 51,7 | 48,3 |

Literatur

- Albrecht-Buehler G: Asymptotically increasing compliance of genomes with Chargaff’s second parity rules through inversions and inverted transpositions. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103. Jahrgang, Nr. 47, 2006, S. 17828–17833, doi:10.1073/pnas.0605553103, PMID 17093051, PMC 1635160 (freier Volltext).

- McLean MJ, Wolfe KH, Devine KM: Base composition skews, replication orientation, and gene orientation in 12 prokaryote genomes. In: J Mol Evol. 47. Jahrgang, Nr. 6, 1998, S. 691–696, doi:10.1007/PL00006428, PMID 9847411.

- Lafay B, Lloyd AT, McLean MJ, Devine KM, Sharp PM, Wolfe KH: Proteome composition and codon usage in spirochaetes: species-specific and DNA strand-specific mutational biases. In: Nucleic Acids Res. 27. Jahrgang, Nr. 7, 1999, S. 1642–1649, doi:10.1093/nar/27.7.1642, PMID 10075995, PMC 148367 (freier Volltext).

- Szybalski W, Kubinski H, Sheldrick P: Pyrimidine clusters on the transcribing strands of DNA and their possible role in the initiation of RNA synthesis. In: Cold Spring Harbor NY Symp. Quant Biol. 31. Jahrgang, 1966, S. 123–127, doi:10.1101/SQB.1966.031.01.019, PMID 4966069.

- McInerney JO: Replicational and transcriptional selection on codon usage in Borrelia burgdorferi. In: Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95. Jahrgang, Nr. 18, 1998, S. 10698–10703, doi:10.1073/pnas.95.18.10698, PMID 9724767, PMC 27958 (freier Volltext).

- Lobry JR: Asymmetric substitution patterns in the two DNA strands of bacteria. In: Mol. Biol. Evol. 13. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 1996, S. 660–665, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025626, PMID 8676740.

Weblinks

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ Elson D, Chargaff E: On the deoxyribonucleic acid content of sea urchin gametes. In: Experientia. 8. Jahrgang, Nr. 4, 1952, S. 143–145, doi:10.1007/BF02170221, PMID 14945441.

- ↑ Mitchell D, Bridge R: A test of Chargaff’s second rule. In: Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 340. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 2006, S. 90–94, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.160, PMID 16364245.

- ↑ Nikolaou C, Almirantis Y: Deviations from Chargaff’s second parity rule in organellar DNA. Insights into the evolution of organellar genomes. In: Gene. 381. Jahrgang, 2006, S. 34–41, doi:10.1016/j.gene.2006.06.010, PMID 16893615.

- ↑ Szybalski W, Kubinski H, Sheldrick O: Pyrimidine clusters on the transcribing strand of DNA and their possible role in the initiation of RNA synthesis. In: Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 31. Jahrgang, 1966, S. 123–127, doi:10.1101/SQB.1966.031.01.019, PMID 4966069.

- ↑ Cristillo AD: Characterization of G0/G1 switch genes in cultured T lymphocytes. Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada 1998.

- ↑ Bell SJ, Forsdyke DR: Deviations from Chargaff’s second parity rule correlate with direction of transcription. In: J Theor Biol. 197. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 1999, S. 63–76, doi:10.1006/jtbi.1998.0858, PMID 10036208.

- ↑ Lao PJ, Forsdyke DR: Thermophilic Bacteria Strictly Obey Szybalski’s Transcription Direction Rule and Politely Purine-Load RNAs with Both Adenine and Guanine. In: Genome. 10. Jahrgang, Nr. 2, 2000, S. 228–236, doi:10.1101/gr.10.2.228, PMID 10673280, PMC 310832 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Chargaff E, Lipshitz R, Green C: Composition of the deoxypentose nucleic acids of four genera of sea-urchin. In: J Biol Chem. 195. Jahrgang, Nr. 1, 1952, S. 155–160, PMID 14938364.

- ↑ R Rudner, JD Karkas, E Chargaff: Separation of B. Subtilis DNA into complementary strands. 3. Direct analysis. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 60. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, 1968, S. 921–2, doi:10.1073/pnas.60.3.921, PMID 4970114, PMC 225140 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ a b Zhang CT, Zhang R, Ou HY: The Z curve database: a graphic representation of genome sequences. In: Bioinformatics. 19. Jahrgang, Nr. 5, 2003, S. 593–599, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg041, PMID 12651717.

- ↑ Perez, J.-C.: Codon populations in single-stranded whole human genome DNA are fractal and fine-tuned by the Golden Ratio 1.618. In: Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Science. 2. Jahrgang, Nr. 3, September 2010, S. 228–240, doi:10.1007/s12539-010-0022-0, PMID 20658335.

- ↑ Bansal M: DNA structure: Revisiting the Watson-Crick double helix. In: Current Science. 85. Jahrgang, Nr. 11, 2003, S. 1556–1563 (eprints.iisc.ernet.in (Memento des vom 26. Juli 2014 im Internet Archive) [abgerufen am 6. Januar 2015]). Info: Der Archivlink wurde automatisch eingesetzt und noch nicht geprüft. Bitte prüfe Original- und Archivlink gemäß Anleitung und entferne dann diesen Hinweis.

- ↑ Hallin PF, David Ussery D: CBS Genome Atlas Database: A dynamic storage for bioinformatic results and sequence data. In: Bioinformatics. 20. Jahrgang, Nr. 18, 2004, S. 3682–3686, doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bth423, PMID 15256401.

Auf dieser Seite verwendete Medien

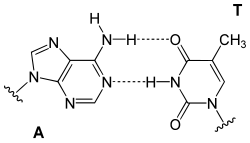

Basenpaar Adenin Thymin (AT)

Basenpaar Guanin Cytosin (GT)